*The Tea Leaf Center is opening up our blog to provide a space and document the voices of those impacted by the recent coup in Burma/Myanmar. The opinions, analysis, and information expressed here are those of the author.*

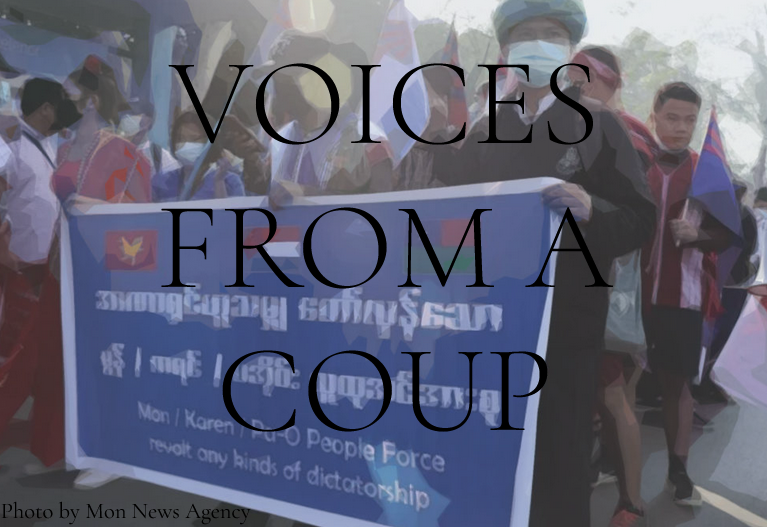

VOICES FROM A COUP

Photo by Mon News Agency

Hoping for Federalism: An Ethnic Perspective

By Psyche

Last week in Thanphyuyat, I was stopped at the toll gate. The soldier there confiscated and checked my phone. I’m used to soldiers checking things: It reminded me of when they checked my ID in Rakhine State. But there’s a feeling of numb panic when someone checks your phone during a military coup.

As an ethnic minority in Myanmar, I have a different lens on the story than most. You see, for many ethnic groups, we distrust both the military and the National League for Democracy. When Myanmar presents itself to the international community, it includes its ethnic groups—even celebrates its 135 accepted races—but in reality, ethnic rights are not given. Ethnic peoples have faced all sorts of violence and discrimination at the hands of the Bamar majority.

In Mon state, our history and language are erased from the national education system. In a country as diverse as Myanmar, ethnic children often do not speak Burmese as their mother tongue, so not bridging between languages in schools disadvantages these children. More than that, our culture is being lost; children cannot write in Mon. And ethnic history is never spoken of in our schools. This is deeply concerning to me: as we lose our language and our history, vital parts of our culture are being lost. So when ethnic people express their distrust of both the military and the National League for Democracy (NLD), remember that many of us see these groups as complicit in erasing the ethnic voice from Myanmar.

Central government power over states undermines state self-determination, further erasing the voices from religious minorities and other marginalized groups in those areas. But this doesn’t just affect educational and religious freedom, it robs those states economically. For example, military projects do not pay tax. Not only do military projects often strip ethnic states’ natural resources, they then do not pay taxes on their extractions. These taxes must be given to the states, and taxes should be divided between the states and divisions equitably. Any deals made involving foreign investment in states should pay tax for that state’s development without fraud and with full transparency.

But in many ways, Mon state is lucky compared to other ethnic states. When I lived in Rakhine, economically the poorest state in Myanmar, there was only one main road in Palawa that allowed a single car to pass. There was no electricity in Kyaw Htaw where I lived and worked as a teacher. When I would ask students what their future dreams were, they would say mainly two things: Either they would dig jade in Kutkai mines (Shan State) or join the Arakan Army. We know that these mines are dangerous, especially after seeing the landslide take over 100 lives in Hpakant the past year. For the girls, they likely will marry young, never pursuing education or careers. And for many children in rural Rakhine, there has been little hope for the future, even under the NLD government. This is the stark reality that people in cities are ignoring. When the ethnic people stand against the military, the military carry out extreme violence against those who are not Bamar. Only under the current coup are the divisions and ethnic states now sharing a deep hate for military cruelty.

While the NLD and military are different, we must remember that the NLD is still under the 2008 Constitution. Their government does not have full power, and so they have worked closely with the military over the past years, seeming at times to ally more closely with the military than the ethnic groups. When the violence broke out in Rakhine, Aung San Suu Kyi expressed gratitude for the military’s service. She said, “Thank you for protecting our home.” Now we are seeing these human rights violations erupt in the streets of Yangon. This is not service to our home. Indeed the very rights that we are losing–internet access, free speech–some NLD members allowed to be stripped from Chin and Rakhine States.

For ethnic peoples in Myanmar, we feel that we have no rights. That is why we have stood against the NLD. For many of us, we don’t want to fight; we only want peace. But the NLD has not allowed for enduring peace. Until recently, ethnic people could do little about this, because our voices were being silenced. Now with the announcement from the interim government of the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), I think there is hope for ethnic groups. The CRPH has finally promised federalized democracy, which has been long hoped for from ethnic peoples of Myanmar.

I am only worried about one thing: I hope that this promise is not like the Panglong Agreement, because that agreement was never finalized. But I do think the CDM will win. And from this, I hope that federal democracy will finally take root in Myanmar.

When the Mon Unity Party (MUP) accepted the Myanmar military’s offer in late February, many interpreted this action to be the MUP looking out for their own power, but it is difficult to know. Perhaps the Myanmar military promised them self-determination. But from history, we know that this promise is not real. It’s fake. So why do ethnic groups like the MUP and Arakan National Party accept? Again, we do not know what the military offered to the ethnic leaders. Sometimes the offers are lucrative to the ethnic leaders. When I heard that the MUP accepted and Aung Lein Oo, the MUP leader, resigned, I resolved to never vote for the MUP again. I gave them my vote, and they broke my trust. Never will I support the Myanmar military government. They have never honored citizens’ rights; they train their soldiers to abuse us. But military children go off to other countries to study at elite universities and sometimes remain abroad. The military educates their children; but they don’t educate their soldiers. They treat their soldiers like you would treat a street dog.

And we have to remember that the military has broken their own 2008 Constitution. In this coup, they stand against their own rules. Thus, clearly there is no meaning in their words in their Constitution, because they have no legitimate reason for this coup’s takeover. We also must remember that under this current Constitution, if the citizens win and the NLD again returns to power, nothing will change meaningfully. In Article 420, the military gives itself authority to take back power. This Constitution must change, or this military takeover will all repeat at a later time.

The MUP is supposed to represent all people’s interests in Mon State, not just for the Mon ethnic group. But we are seeing divisions arise between people. For example, in Loikaw, there is an ethnic party leading for the demonstrations, but the NLD supporters do not like this, so now they separate. This is dangerous, because this is the time when we should stand against one thing: The unconstitutional military seizure of power. We must stand for our citizen rights. If we divide, then we will be two against one: easily broken. The military knows this: It is their strategy to take us down easily. Only together are we strong enough.

I will never accept this coup as the real government. On 1 February, people in my village were having trouble with accessing the internet, and some said it was because the military was taking power. But then that night when we heard the news confirmed, I felt so horrible. And since that day, we have continually lost our rights. For 60 years, we have endured this coup government. And for most ethnic people, NLD has not brought the real federal democracy that was promised with the Panglong Agreement.

Many of my friends see the coup as just a fight between the NLD and the Myanmar military. From their perspective, ethnic rights have been humiliated for so long. But for others of us, we see the connections between all of the people in Myanmar now. For me, the story of those in Rakhine has become more connected to my own experience: They could not vote; I could vote, but now that vote is worthless. We both now have experienced times with no access to the internet. Before the coup, when the military killed the Rohingya, the government brainwashed the populace, saying that these people are not Myanmar people. But the Rohingya want rights just the same as any other person living in Myanmar–and even more broadly–same as any other human across the world. Other people my age are waking up to this and posting about Rohingya in a positive light. It is my first time seeing this.

Just as Rohingya are excluded from Myanmar society, we need to consider how to include other outsiders. In the current situation, we often exclude military children. This is a time to welcome the children and teach them about human rights. They can also take part in this movement for democracy.

So, even though I do not trust Aung San Suu Kyi–that’s just my personal opinion– this coup must be fought together. And the ethnic voice must be heard and valued. Every Myanmar citizen who takes part in the Civil Disobedience Movement should consider the ethnic or minority religious views. The government has been brainwashing us indirectly, telling us what is good and what is bad. And we accept it. For the ethnic groups, the military divides us: Mon are Mon; Rakhine are Rakhine. But now even within ethnic groups, we are fracturing into groups, for instance how Kayin unity was divided into DKBA and KNU. The MUP now has divisions. I believe that religions actually share more in common than we commonly think, but the tactics of the military separates religious communities. Now more than ever, we have to work together.

The Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) has issued a statement promising to “build a federal democratic republic that is for the people, of the people, and by the people.” This is the only way forward: The NLD must include all people in Myanmar to work towards this vision. I think if the international stage can pressure the Myanmar military, supporting the Myanmar people standing against this dictatorship, maybe we can win our freedom. Right now, we don’t know what conversations the CRPH is having behind closed doors. And even if we don’t know where Daw Aung San Suu Kyi or U Win Mint are, we must go out and protest nonviolently.

I stand against all the dictatorships everywhere. Honestly, sometimes I am not proud of being a Myanmar citizen. I feel like the world looks down on Myanmar, because the military continually takes power through coups. Even when we go overseas, many countries see us as poor migrants or cheap labor. For the military, they do not care about the welfare of their people, especially for the poor. If we support the military, there is no way forward. This is our chance for federal democracy. In the new Myanmar, I hope for a colorful democracy that includes everyone, working together in peace.